Editor's Note: We're experimenting with publishing editorial writing and criticism about New Art City worlds and other new media art exhibitions on our blog. If you love it, hate it, or have an idea for a piece you want to write, get in touch! We want to hear from you. --Benny

More than a century ago, the traveller and horror-story writer Lafcadio Hearn sat in a Kyoto hotel room, enamoured by the silhouettes that adorned his shoji—the paper screens typically found in traditional Japanese architecture. During the day, he noticed, they were animated with shadows cast by the flora outside. Conversely, at night, they were a canvas for shades of domestic interiority. Hearn wrote about the perceptual playfulness of shadows in his journal: “Very possibly all sense of art, as well as all sense of the supernatural, had its simple beginnings in the study of shadows.”

Shadows have been our companions for as long as the world has spun around the sun. They are virtual beings—not physically existing as such, but made to appear so by our physical interference with light (and a touch of our perceptual creativity). They are restless, shapeshifting creatures whose presence confirms our own humanity. Vampires, for example, don’t possess shadows because they are not of this world. Shadows cling to our earthly forms; following us, scuttling around, caricaturing us—stretching themselves long and then suddenly shrinking or disappearing altogether. They occupy a liminal territory between us and the imagined realm, between the material and the metaphorical, the physical and the metaphysical. Throughout our history, we have cast them as our guardians; as subterranean, unknowable selves; as places of refuge and danger alike.

Still image taken from Disinformation's "Abstract_Untitled" (2021), a video work created from images of high-voltage electric discharges. View in context ➝

The electrification of the modern world has often been bemoaned by certain aesthetes as an affront to the beauty of shadows (perhaps most famously in Jun'ichirō Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows). The omnipresence of light threatens to devour shadows, or at least rob them of their powers. But from the perspective of the audio-kinetic art project Disinformation (brainchild of Joe Banks), this couldn’t be further from the truth. Specialising in sonic art created using electrical interference and electromagnetic noise, Disinformation celebrates the power of electricity to conjure up new arenas of shadows and shadow-making: as sound.

Commissioned by Schemata Arts (Corsica Studios) and brilliantly curated by Alice Hoffmann-Fuller, the virtual exhibition “Antithesis” explores this world of sonic shadows inside a 3D digital rendering of the physical Corsica Studios venue. Launched in January 2022, it features a collage of new and archival work by Disinformation: 25 sound works, 24 of which are recordings and/or remixes of electromagnetic noise, and 7 video artworks.

"Kwaidan, Part 3" by Disinformation (2005)

Where do virtual spaces exist?

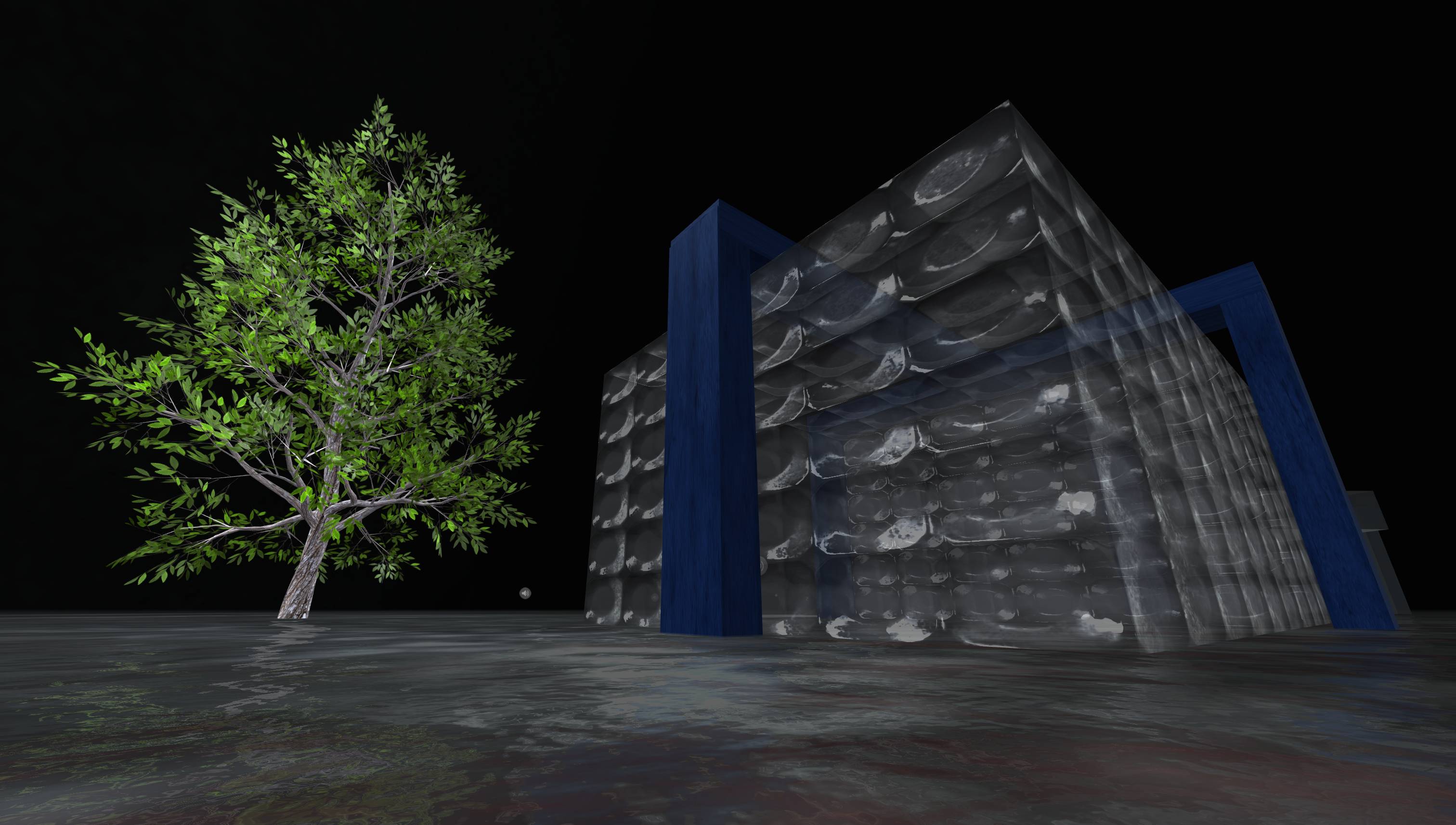

At the beginning of the exhibition, we find ourselves outside Corsica Studios. On our left, an assortment of giant metallic shards resemble the form of a succulent plant. On our right, a memorial to the electro-genius Michael Faraday—reconstructed in glass instead of steel, the way its brutalist architect Rodney Gordon had originally intended it to be (with the aim of displaying the inner workings of the electric substation housed inside it). Next to it, the only splash of colour in this scene: the bright green leaves of a lonely tree. The floor seems oily, murky, reflective. A spotlight hovers over the entrance of the studio—the source unknown. I hear distant rumblings, crackles, buzzing; the whip of electrical activity. It’s a bit worrying, given how damp the air feels. This is not how we usually experience an exhibition, but that is the point.

Photo of the real Faraday Memorial at Elephant Square in London. By Images George Rex from London, England - Faraday Memorial / SE1, CC BY-SA 2.0

Screenshot of Hoffman-Fuller's digital rendition of the Faraday Memorial. View in context ➝

We are guided towards the memorial and the tree. The sounds grow louder.

Virtual spaces offer an exciting array of curatorial choices, and Corsica Studio’s Alice Hoffmann-Fuller—who designed the exhibition space—seems to have made the most of its potential, offering an exhibition space that doesn’t attempt to substitute the physical space of the real-life studio but, instead, takes full advantage of the virtual medium. In an email exchange, she elaborates on the liberating nature of virtuality: “I wanted to explore a new way of looking at how we present sound online and in a spatial environment, where the user can interact with how they hear, and also personally “mix” a piece according to their position and proximity—something I couldn’t have dreamed of achieving in the physical world,” she says. “The fact that pieces can be arranged to overlap, that their independent volumes and spatial surround sound can be used to create soundscapes that are highly editable—it’s not often that the user and artist can work in tandem to make a bespoke, individual listening experience. This even surplants the artist/viewer feedback loop that comes from performing live.”

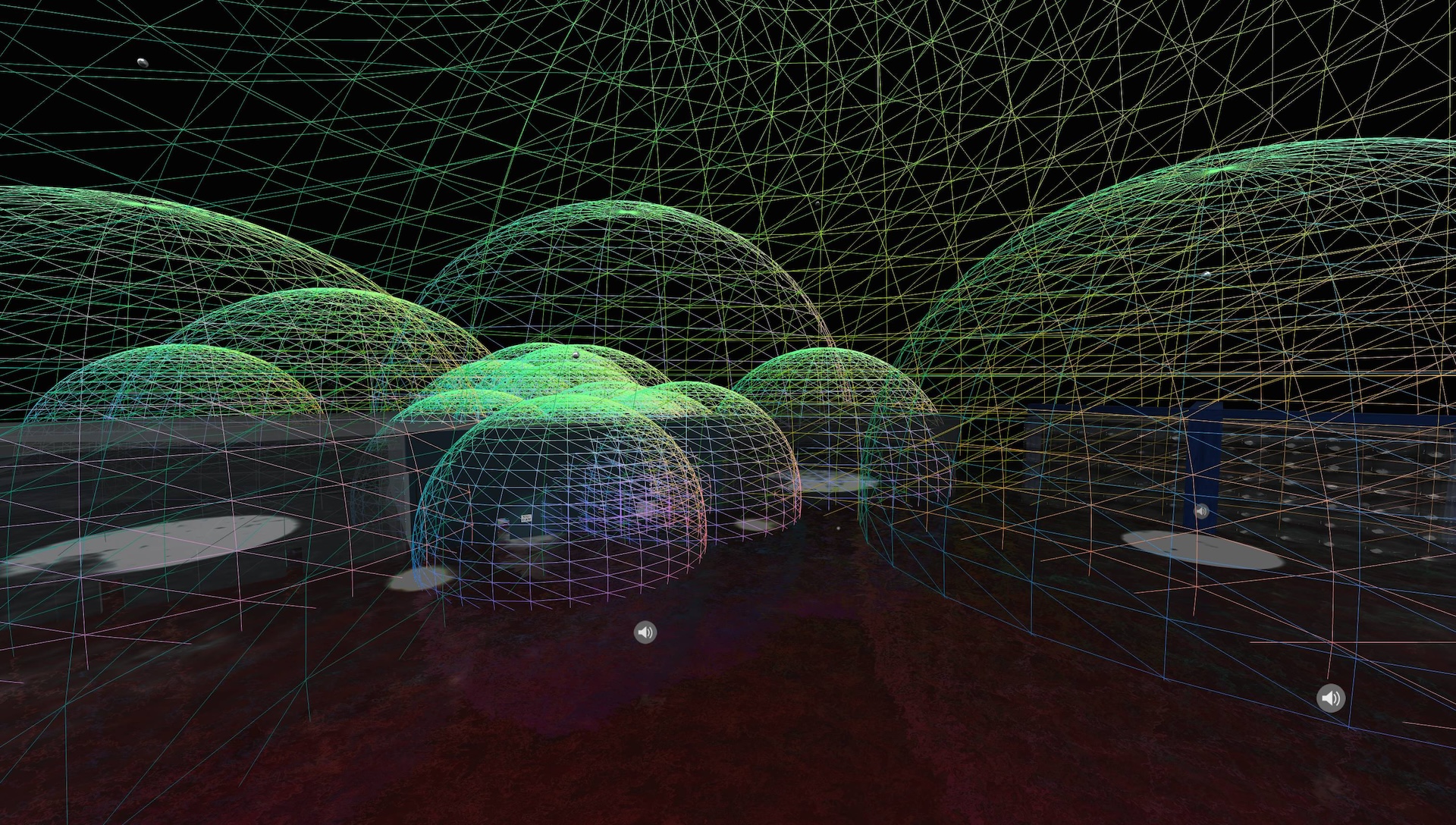

A screenshot from behind-the-scenes—intersecting wireframe spheres show the huge number of audio works that Hoffman-Fuller meticulously curated and placed to build Antithesis.

Banks agrees: “In that sense, Antithesis is a kind of spatial remix engine.”

At the same time, however, Hoffman-Fuller is wary of talking about virtual spaces as some sort of recent phenomenon that posits a radical rupture from art-making as we know it. She introduces me to a paper on Virtual Space Theory by the architect Or Ettlinger in which Ettlinger presents an image of Peter Breugel the Elder’s painting, The Tower of Babel (1563), and asks: where is this tower; where does it exist? The tower doesn’t exist in a physical dimension, so where is it? Is it in the picture; in our imagination; in Breugel’s imagination, in Babel? Ettlinger concludes that the tower exists in a virtual space—which he then defines as an immersive illusion crafted by the artist through a manipulation of perspective. Hoffman Fuller concurs with this analysis: “It expands on the idea that virtual space has existed since humans created any kind of picture, which can transport the viewer into a virtual representation in which the viewer can immerse themselves.”

Pieter Bruegel The Elder's "The Tower of Babel" (1563)

Perhaps art has always been about deploying illusions to create virtual experiences. If art was always virtual, then what can be said about galleries and theaters, the spaces where art is curated and experienced? Corsica Studios has a physical location in London. So does the Faraday Memorial, made of steel instead of glass. Where do the virtual models of Corsica Studios and the Glass Faraday Memorial exist?

Virtuality, then, is perhaps nothing new—it has simply expanded into new territories. The exhibition space is entering a virtual stage; entering the world of illusions usually reserved for art. This allows the exhibition space to become even more integrated with the works curated inside it, blurring the line between art and space; curation and performance.

"National Grid" by Disinformation (2022) - featuring live mains electricity, electronic tanpura, spring reverb and virtual string quartet

Electricity — a versatile cosmic force

As I move towards the Faraday Memorial, the sounds become more distinctly audible: an electric wail, eerie strings and drone notes organise themselves into a ghostly, meditative piece of music. This piece is part of Disinformation’s updated rendition of National Grid, combining sounds derived from live mains electricity with electronic tanpura and a virtual string quartet. Inside one of the rooms of the studio, there is a video installation based on a previous version created in collaboration with the filmmaker Barry Hale.

This raw and visceral concert version of National Grid, performed in collaboration with Strange Attractor (Mark Pilkington), showcases the fundamental rhythms of electricity production, and the roar and grind of processes that result in its distribution at the astounding scale we take for granted. The sounds here are volcanic and thunderous, a parade of percussive noise, a visceral force—wildly different from the ambient drones found outside. On one hand, electricity is demystified here, stripped bare to its brutish elements. On the other, the very act of demystification reveals its miraculous reality, celebrated here as a sort of spiritual awakening.

Still image taken from Disinformation's "National Grid" (2001), a video collaboration with Barry Hale, featuring footage of UK National Grid transformer stations. View in context ➝

This juxtaposition speaks to the power and versatility of electricity as a cosmic force that pervades experience at every level—it is the words you’re reading on this screen, it is also the virtual sensations, emotions and memories that make you who you are. “Part of the conceptual basis for the sound work National Grid is the idea that this piece is a sonic tribute to ‘the creative genius of electrification’,” says Banks. “Notwithstanding environmental costs, the idea that electrification itself is a form of infrastructural art project […] which facilitated other forms of creativity which people mostly take for granted—from cooking with electrical appliances to electronic communications and electronic music, etc.”

Electricity is ubiquitous not only in our environment but within our biological systems, as an engine of neural activity; firing of signals between synapses, creating complex virtual experiences such as memories, feelings, etc. The Scintillating Scotoma video is an optokinetic artwork, which explores the notion that perception itself is an electrically mediated biological system. The video simulates the shimmering and flickering distortions which disrupt vision—often experienced by those who have migraines and epileptic seizures—when certain electrophysiological waves reverberate across the cerebral cortex (the term was devised by the 19th century physician Hubert Airy, from the Latin “scintilla”, meaning “spark”, and the ancient Greek “skotos”, meaning “darkness”).

Still image from Disinformation's video work, "Scintillating Scotoma" (2021). View in context ➝

Ghosts in the Machine — when our perceptions short-circuit

These cognitive and perceptual disturbances caused by bioelectrical processes constitute another thematic mainstay of Disinformation’s work: ghosts; of events, of the past, of imagined futures. In 1999, Banks initiated the Rorschach Audio project as a critique of Electronic Voice Phenomena research (of the making and promotion of alleged ghost voice recordings) in parapsychology and in the arts, before expanding to take-in a much broader range of phenomena associated with ambiguities of hearing, and phenomena of aural, visual and linguistic perception.

“The central concept in Rorschach Audio”, explains Banks, “is the idea that the way the brain perceives distorted, obscured and/or very quiet speech sounds resembles the way people 'see' faces of monsters, angels, demons etc. in Rorschach ink-blot tests.” The idea was to debunk superstitions emerging out of misunderstood electrical phenomena, but it led Banks to develop an interest in the psychology of belief and the creative power of perception. In one of his articles, he concludes: “the process of reading meanings into artworks is simply an extension of processes which are hard-wired into everyone’s perceptual mechanisms.”

We dream up ghosts using the same faculties we use to interpret art. Sure, the nexus of superstition and power is one that deserves criticism. Banks draws my attention to the case of the Indian anti-superstition campaigner Narendra Dabholkar, murdered in 2013, whose death was openly celebrated by the Hindu nationalist group Sanatan Sanstha. However, to understand why we believe in ghosts, it is perhaps necessary to ask the question: what do ghosts mean to us?

Still image from Disinformation's video work, "Untitled_Eye" (2021). View in context ➝

Apparitions give a shape to our fears, anxieties and, sometimes, hopes. Ghosts appear as disturbances, interruptions, consolations. Their existence is predicated on a sort of non-existence (or immateriality) that has an intrusive power over our lived experiences. Many of the installations here are about how we perceive the virtual residue of electrical phenomena as something supernatural (another one of the many reasons why this format suits the exhibition so well). Ghost Shells, for example, showcases geomagnetic whistlers produced by lightning strikes which German army-field telephone operators, in communication equipment, heard as "ghosts" of artillery shells whistling across WW1 battlefields. Banks takes the white sheet off these ghosts to reveal our own cognitive blind spots. But, looking at the triumph of anti-scientific forces on the world stage, I can’t help but wonder why certain beliefs are impervious to the obvious.

Perhaps, our ghosts serve as an antidote to the tragedy of mortality, the absence of lost friends, the virtuality of the past, the uncertainty of the future. Where then should ghosts go? How do we rescue them from the clutches of superstition?

Banks shares a pertinent quote by the poet Ivan Chtcheglov: “All cities are geological; you can’t take three steps without encountering ghosts bearing all the prestige of their legends. We move within a closed landscape whose landmarks constantly draw us toward the past. Certain shifting angles, certain receding perspectives, allow us to glimpse original conceptions of space, but this vision remains fragmentary. It must be sought in the magical locales of fairy tales and surrealist writings: castles, endless walls, little forgotten bars, mammoth caverns, casino mirrors…”

This is where our shadows and ghosts find peace: in literature, in art, in music. This immersive world of artistic illusions and make-believe is where our senses surrender to the imagination without diminishing our critical faculties; where we find comfort, wisdom and wonder in the magical world of earthly delights; where we simulate a virtual existence beyond our own, worlds apart from our own. These ghosts don’t speak to us of an after-life, but of hope that another world is possible here and now. They lean forward and whisper into our ears what Banks refers to as “the most romantic notion that mankind has ever conceived: seize the day.”

———————————————————————————————————————

The track “Doppelgänger Variations”, featuring Disinformation in collaboration with the renown American tap artist Savion Glover, appears on the 12" vinyl compilation “Cire Noire”, released by Sähkö Recordings on November 24, 2023.

Disinformation + Strange Attractor's "Circuit Blasting" is available through the Adaadat label website.