In this Article 🗒️

- Archiving digital art is difficult because digital media is complex and fragile.

- Owning the means of running and displaying your work is empowering and it increases the work's longevity.

- You can now download your NAC worlds and host them independently, put them in a gallery, or give them to your grandkids on a floppy disk.

Archiving digital artwork is difficult for many reasons. One of the biggest challenges is compatibility. Besides digital images and videos, most digital artworks (e.g. games, interactive media, performances etc.) depend on specific pieces of software, which run on specific operating systems, and specific hardware. There are so many layers of abstraction behind digital media, and all of them — the software, the operating system, the hardware — are necessary to get a work of digital art to do anything at all.

Unlike with physical stuff, if a single piece of this technological stack is missing, if even a single semicolon is out of place, the whole show is over. When digital stuff fails, you don't even get to hold the broken thing in your hand, look at the springs and gears, and imagine how it might have worked. When trying to resuscitate old digital art, you're lucky even to see an error message. Most of the time, simply nothing happens at all.

Lucky for me, and everyone else who likes to explore the bizarre and endearing things people got up to on their computing machines over the last several decades, there are digital archivists and historians, people who specialize in making digital things last, documenting them, and telling their stories.

A screenshot of Preserving Worlds, a documentary tour through old, abandoned virtual spaces (taken June 20, 2023)

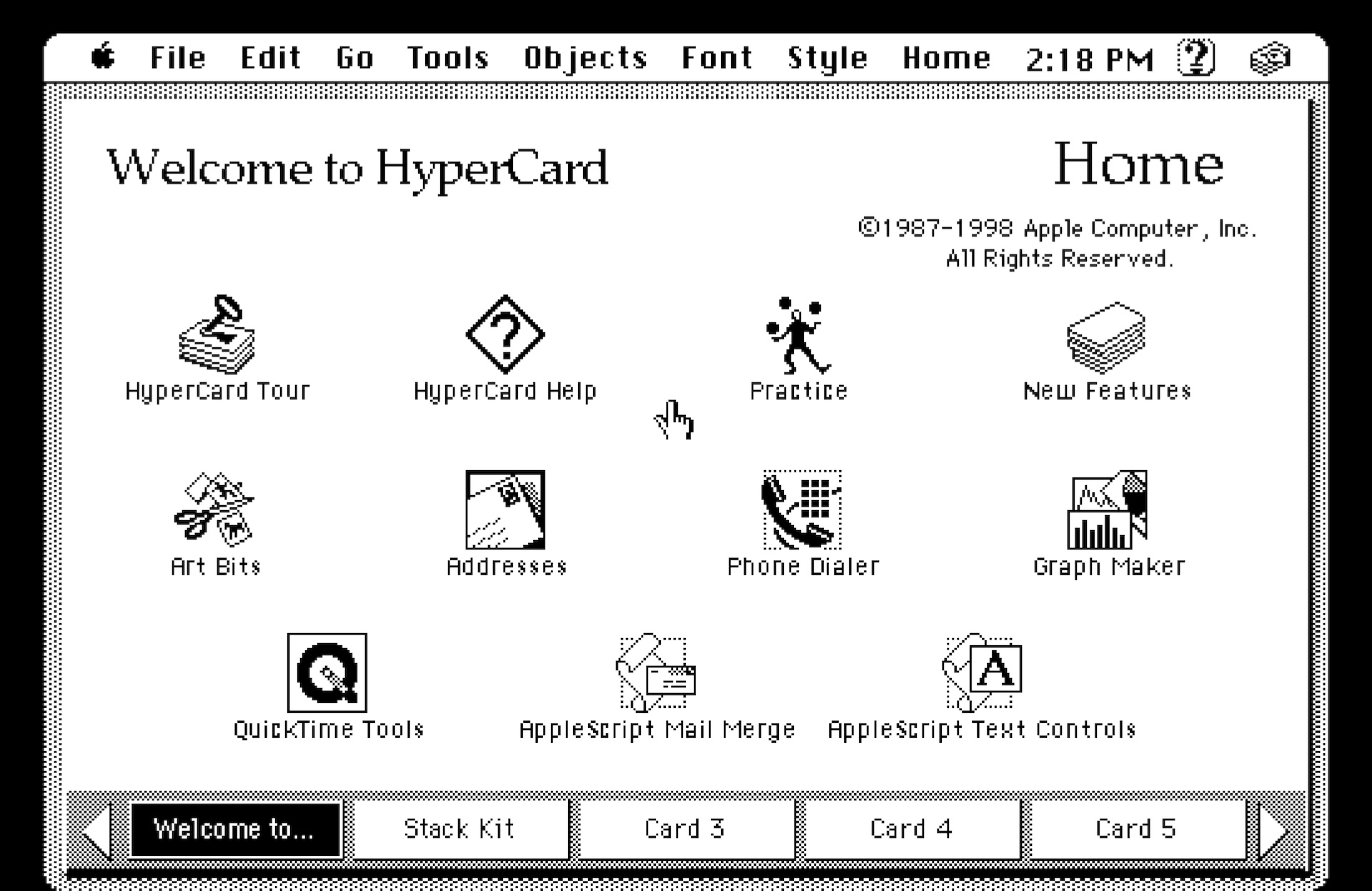

A common solution to the problem of preserving digital art (and other kinds of computation) is to build virtual simulations of all the pieces of technology required to make the old program run (a.k.a. "virtual machines"). For example, here's one of my favorite virtual machines made available by the Internet Archive that lets you run HyperCard in your web browser — part of their larger Emulation Station project.

A screenshot of the Internet Archive's Macintosh System 7.5.3 virtual machine running HyperCard in a modern web browser (taken June 20, 2023)

In fact, one of the rare exceptions in the repeating history of digital-things-that-quickly-become-obsolete is the website. Today, in a completely modern web browser, you can still successfully view the very first web pages ever created some thirty years after they were made. Why does this work? Why don't websites become obsolete as quickly as other software?

The everlasting world wide web

HTML, the language of websites, began as a small and open standard, easy to read, write, and adopt. Since you didn't need expensive private software to create a website, anyone with a text editor could and did author content and put it online using free web hosting services like GeoCities or Angelfire.

A snapshot of GeoCities from Dec. 20, 1996, recorded with the The Wayback Machine (screenshot taken June 20, 2023)

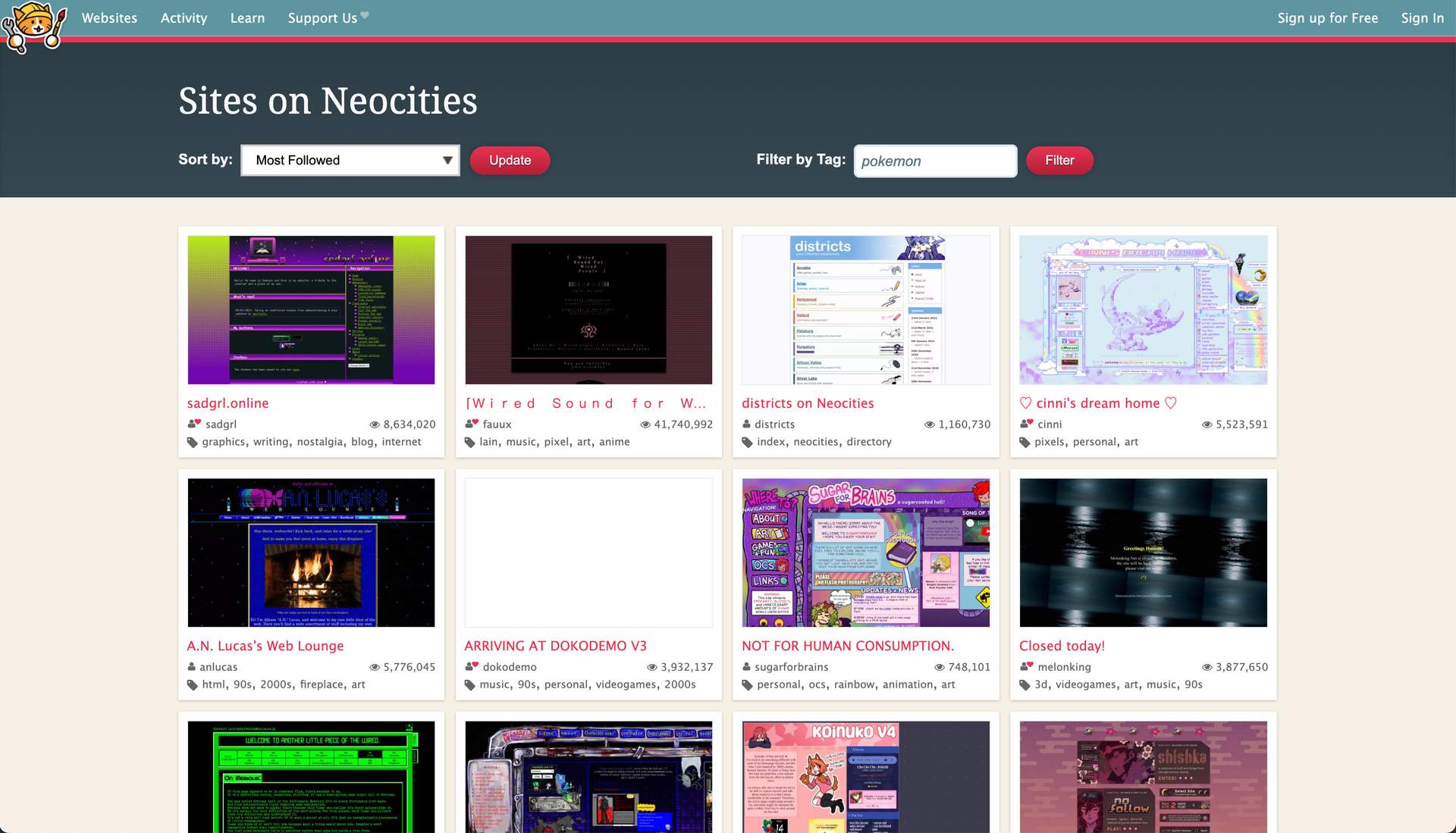

GeoCities no longer exists, but today we get to enjoy its spiritual sibling, Neocities (screenshot taken June 20, 2023)

Over time, new features were added to HTML, but older websites written in older versions of HTML never went away. Browser companies competed to build the most popular web browser, so they had to support both the new and improved websites as well as all of the old content that was still online and would never change.

Meanwhile, some people started to recognize how special and open this internet thing was turning out to be, so they formed web standards groups to protect it from privatization. They advocated for standard, accessible ways of writing webpages. This guidance, combined with the competition between browser developers, resulted in a World Wide Web today that is remarkably backwards compatible (with some important exceptions, like flash and java applets).

Dead links

Another large part of the difficulty of archiving online digital media is that it often disappears. Compared to normal computer programs, web applications are unique in that you don't install or save them — they don't live on any storage device that you have access to. Once you close your browser tab, the website is gone until you visit the URL again.

This means that if the individual who hosts the website gets tired of paying their web hosting bill, if their firm shuts down, or if someone simply makes a mistake (see myspace), the website and all of the content on it can vanish.

The key to solving this problem is putting the data back in the hands of the user.

Tools like Conifer / Web Recorder and the Wayback Machine give you the power to create and store snapshots of websites you care about (that's how I took the screenshot of Geocities from 1996). Activist groups like Archive Team coordinate emergency efforts to preserve online culture before it is erased. Tools like Distributed Press help you publish content online in a way that is less prone to a single source of failure, and more suitable for long-term archiving. And social media standards like ActivityPub (recently popularized by Mastodon) are trying to do for social media what HTML did for the web in general: take some of the power currently monopolized by technology firms and move it back into the hands of users.

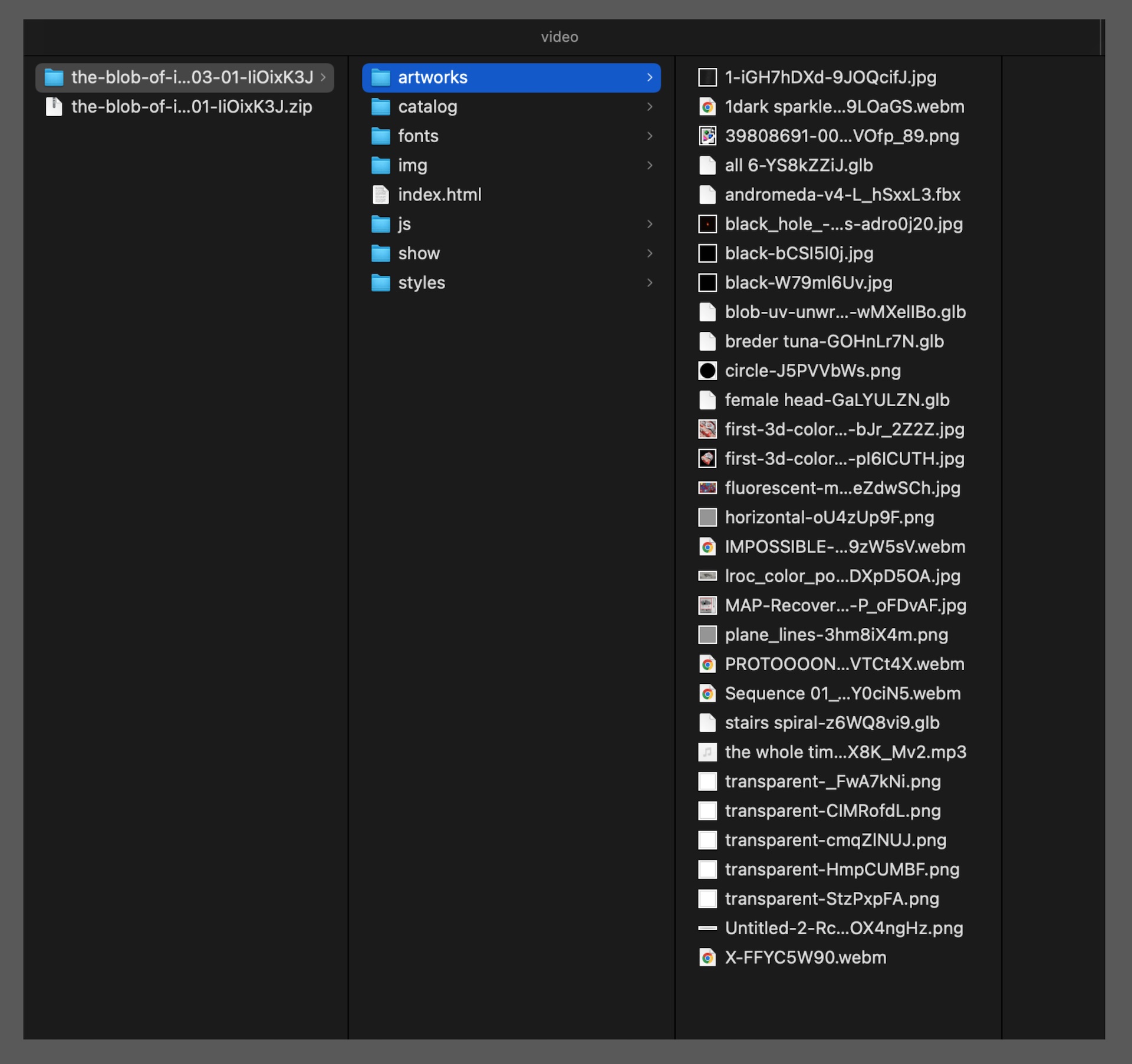

A New Art City world is a website

In order to take advantage of the backwards compatibility and archivability of the web, we built a way to export New Art City worlds as self-contained websites. New Art City supporters can now download their work as a complete directory of HTML, CSS and JavaScript files. A downloaded archive looks something like this:

What you are looking at are all the pieces that make a website (HTML, CSS, JS, fonts, images, etc.) When you host this directory with a simple web server, you'll see your complete world, exactly like when it is accessed from the New Art City homepage:

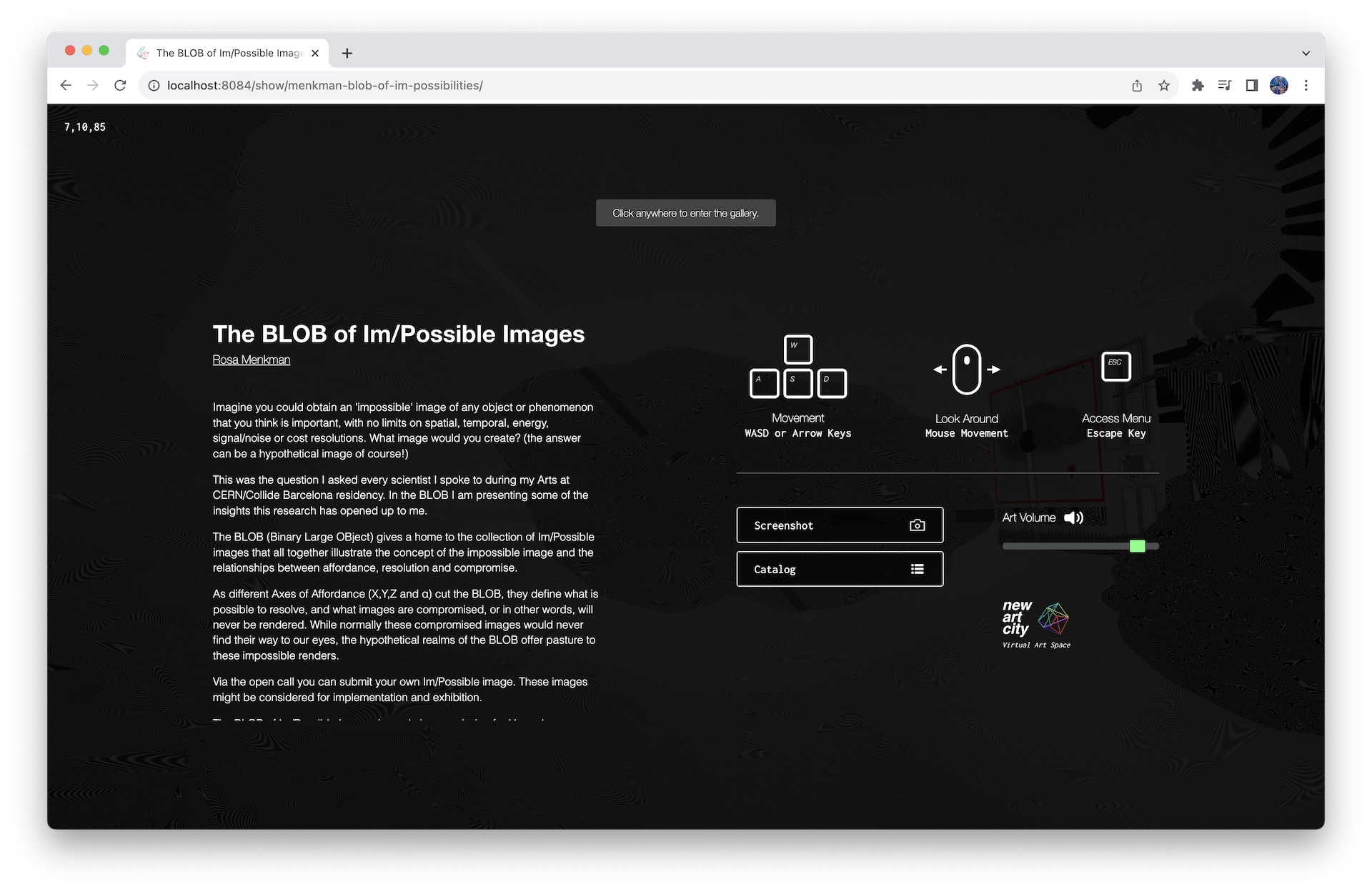

Rosa Menkman's The BLOB of Im/Possible Images accessed offline from a world export

You can do anything you want with your archive: host it on your own website, sell it, put it in a library, on a floppy disk, on the decentralized web, or in a dead drop. And since it runs on a web browser today, it is likely to keep running on web browsers in the future.

For the last year and a half we've been collaborating with Rhonda Holberton at CADRE (see the fascinating archives of the SWITCH New Media Journal) and more recently Nick Szydlowski at the SJSU University Library to work toward archiving new and historic digital media art. The world export feature is an important milestone in this effort.

We're proud to share this shout-out from Dragan Espenschied, director of the digital art preservation program at Rhizome:

I've been working online for more than two decades, at first as a net artist, and later as a conservator of net art. So many times I witnessed digital artists committing to platforms that in many cases were started with best intentions, but ultimately had to close down, more than once taking years of work and community production with them.

That's why I was thrilled when the folks from New Art City contacted me to discuss initial ideas about providing their users with the ability to export works created and published on NAC as standalone files. This allows for NAC exhibitions to be uploaded to any web hosting service, including artists' own websites, and to much more easily become parts of archives and collections, and receive preservation treatment.

By planning and implementing this feature well ahead of any possible trouble the platform might face in the future, the team acted in the best interest of artists. That is how you become a great platform steward. — Perhaps this can also encourage artists to look out for similar export features on other platforms they're active on, and demand implementation when they're not offered.

Digital art doesn't have to be a perpetual building-from-scratch process, it should benefit from interesting developments and a high quality discourse that spans decades and artistic movements.

Since 2020, we've hosted hundreds of online exhibitions, inlcuding the work of thousands of new media artists from all over the globe. The stories people tell on New Art City are beautiful, chaotic, messy expressions in a new medium. We want this work to be accessible for decades to come.